On a quiet back road in industrial Dandenong, in Melbourne’s south-east, an enormous factory rises from the horizon as you approach.

It’s Australia’s newest car manufacturing plant, which is not a sentence anybody from 2018 would have imagined being written ever again.

As part of an ambitious investment – and vote of confidence in Australian manufacturing – the $116 million plant opened in November 2025. It is the new home of Walkinshaw Automotive Group, which used to effectively call itself Holden Special Vehicles (HSV).

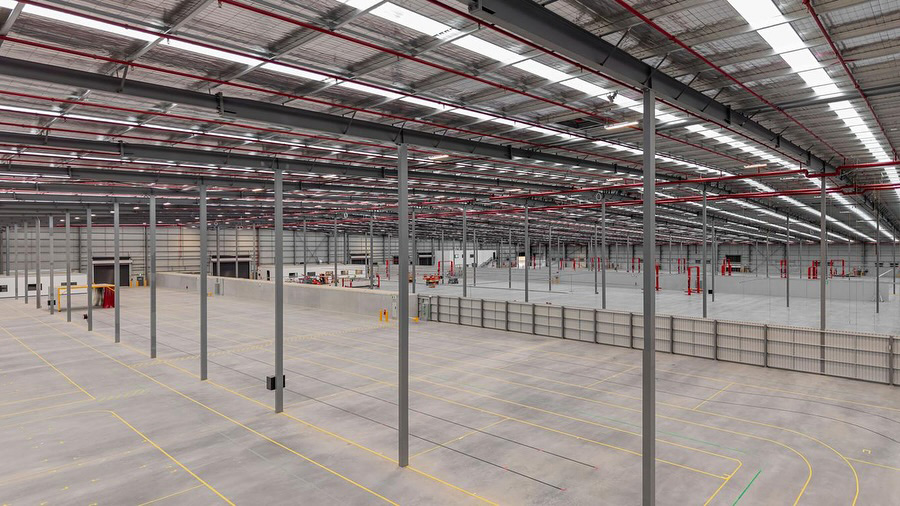

Under this one roof covering 53,000 square metres, Chevrolet Silverados and Dodge Ram pick-ups are converted from left- to right-hand-drive for the Australian market, while production of the forthcoming Volkswagen Amarok W600 will commence here shortly, as well as the design, engineering and preparation of Walkinshaw Andretti United’s new Toyota GR Supra factory Supercars team.

Walkinshaw is also managing the left-to-right conversion program for the Toyota Tundra and GMC Yukon. Altogether, the brand is now producing more than 13,000 vehicles each year.

It was quite a journey to get to this point, Walkinshaw group commercial director, Oliver Lukeis, tells Open Road.

Holden shuttered its South Australian factory in October 2017 and by December 2017 the final hotted-up Commodore had rolled off the production line at HSV’s Clayton factory in Victoria – bringing the curtain down after three decades and 90,114 vehicles built.

The Holden Commodore was no more, but Walkinshaw still had a team of world-class designers and engineers, and low-scale manufacturing expertise, working with global car manufacturers.

“In 2017, we moved out of the [original HSV] site in Rayhurst Street, Clayton, which is currently being demolished,” says Lukeis. “But even when we were there, the walls were just being held up, and they had metal structures trying to support it.

“We embarked on a journey to our previous facility at Whiteside Road and during that time, Holden was ceasing production in Australia and we were embarking on programs like left-to-right conversions and our first Amarok with the Volkswagen team. And at that time we didn’t think that we’d be able to fill the site that we had just commenced the lease for in Whiteside Road.”

But the former HSV opened its engineering and manufacturing services to more clients, and within a few years it had seven sites scattered around south-east Melbourne.

“Once you start to proliferate off-site, you start to duplicate your costs across security, cleaning, engineering, staff travelling site to site… so we wanted to really bring all that back on [to the one site],” says Lukeis.

Having identified the site of the current factory, the first sod was turned in June 2020 and on November 17, 2025, the opening ribbon was cut.

— Oliver Lukeis, Group Commercial Director at Walkinshaw

A sprawling carpark services the building, while in the reception area, two of the last and greatest hotted-up HSV Commodores take pride of place, including the seminal GTSR W1, possibly the greatest Australian performance vehicle ever produced.

Situated on 120,000 square metres of land, the factory has five production lines covering 25,000 square metres, a 7000 square-metre engineering facility, and a 12,000 square-metre warehouse able to accommodate more than 12,500 pallets.

The building also has space for the Walkinshaw-Andretti United Supercars team, extensive corporate office space, storage for 400 vehicles and parking for up to 730 employees, as well as capacity to scale up to 1500 workers when running on all cylinders.

Lukeis says one of the biggest game changers has simply been taking previously U-shaped production lines – bent and twisted to fit into square-shaped factories – and making them simple straight-lines, 110 metres long.

“Sounds quite boring when you’re talking about the logistics of parts, but for us it was an absolute headache, because you’re trying to take containers of goods to multiple sites and all those things start to add up on the business,” he says.

There’s also an electrical lab on-site, HVAC test chamber, rapid prototyping 3D printing capability and a structures lab with a four-post rig. Walkinshaw’s factory is also an ADR-registered test facility.

New capabilities include a larger environmental chamber with vibration testing, a photometric lab and engine dyne, while the building itself is hydrogen compliant.

Basically, everything you need to design and engineer a car from the ground up – and then build it.

Walkinshaw has the engineering expertise, design studio and manufacturing capability – not to mention a world-famous name and a shiny, enormous new factory. Meanwhile cashed-up car collectors continue to shell out millions for special supercars. Would the brand ever do a low-volume car to show off all this expertise and capability – like a supercar?

“We’d love to,” says Lukeis. “If the timing and everything aligned … I know Ryan [Walkinshaw] would be a massive fan of being able to make that happen.”

Lukeis says Walkinshaw is currently inundated with work – a good problem to have – but some sort of homegrown car is on the radar.

“It’d be great to do one as a concept and kind of show off some of the expertise that we have,” he says. “I suppose we’re in a position where we don’t advertise a lot about what we do because we’re working with customers and it’s up to them how they want to sell our services and our product… whereas if we did build a concept vehicle that showed off all of our capabilities, then that’s a great tool that we’d be able to use to be able to expand the knowledge of the Walkinshaw business in Australia.”

Lukeis says that while Walkinshaw is helping write a new chapter for low-volume car manufacturing in Australia, the days of large Australian-based facilities and busy production lines producing thousands of mass-market vehicles seem to be over for now.

“I think it’s really difficult because you need the supply chain to support it,” he says. “If you look back to what happened during the exit of the OEM manufacturing in Australia, once one or two decided that they were going to cease manufacturing, then it all disappeared because the surrounding supply chain is so important. And now that that capability has been given up, to do large parts, to be able to have large injection-moulded tools, to be able to do large stampings, [that’s all now gone].

“You’d be really restarting the whole industry from scratch, not just an OEM coming in and producing a car. Restarting a whole industry, that would require immense support.”