At a Glance

Solid state batteries (SSBs) have long been the catch-cry of automakers keen to find an advantage in the evolving and growing electric vehicle market. They differ from the lithium-ion batteries used in today’s EVs by replacing the liquid electrolyte with a solid material, promising safer packs with higher energy density, faster charging and potentially longer life — all of which could translate to longer-range EVs without extra weight.

There have been multitudes of announcements over past years by major automakers, big tech and specialist battery makers claiming in-roads to commercially viable solid state batteries. As yet though, none have come to fruition.

The technology has struggled to reach mass production because solid-to-solid interfaces can create high resistance and degrade over time. Lithium dendrite “fingers” forming between battery components can still cause shorts and reduce charging speed, battery life and capacity. To add to that, going from the lab to the factory has proven complex and costly to scale to automotive-grade volumes.

Some experts predict that commercially viable solid-state batteries will be used in premium EVs and other applications such as drones and robotics by 2030. The latest announcement, by Estonian-based startup Donut Lab, claims to have solved many of the barriers to a viable SSBs, including energy density, cycle life, charge rate, safety, and cost.

Donut Lab says its battery is good for 100,000 cycles (25-50 times that of the average EV battery today), that it can recharge in five to ten minutes, and is cheaper to make than average lithium-ion batteries. They say it retains 99 per cent of its capacity between -30°C and over 100°C, meaning no range loss in extreme temperatures, and say it is not subject to thermal runaway (the chemical phenomenon that can cause li-ion batteries to “catch fire”).

Perhaps most interestingly, the company claims this production-ready battery has an energy density of 400Wh/kg, which theoretically could make it useful for electric flight if the pack-level energy density adds up. However, for the moment Donut Lab is planning to use its SSB in motorbikes.

Industry experts, however, question the veracity of Donut Lab’s claims, amid a lack of technical detail (exact chemistry and metals, for example), and say that long-term performance results and independent data is needed. Battery rival Svolt has gone so far as saying Donut Lab's “parameters are contradictory”. It has its bets pegged on semi-solid state batteries, which use a gel-like or partially liquid electrolyte mixed with solid material, and can be more forgiving than all-solid electrolytes.

This latest announcement brings up the question, however: What is a solid-state battery, and why do they matter? And how soon can we buy EVs with solid state batteries?

There’s a reason solid-state batteries keep appearing in the news. Today’s lithium-ion packs last longer and perform better than those made a decade ago, but they still rely on a liquid electrolyte that needs careful thermal control and robust pack engineering. Solid-state cells, at least in theory, open the door to higher performance, longer life, lighter packs and faster charging.

It’s also worth noting that “solid-state” isn’t one single battery. There are multiple electrolyte types (oxide, sulphide, polymer), plus plenty of hybrids that still include some liquid or gel. So when a company says “solid-state”, it pays to ask exactly what they mean.

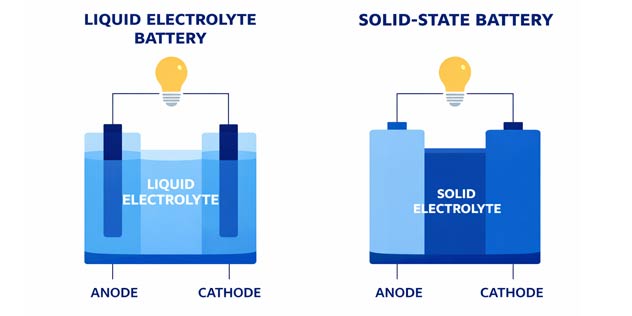

A solid-state battery is a rechargeable battery that uses a solid electrolyte instead of the liquid electrolyte found in most lithium-ion cells today. The electrolyte is the material that carries lithium ions between the cathode and anode during charging and driving. Solid electrolytes can be ceramic, polymer, sulphide-based, or a hybrid mix. Many solid-state designs also switch graphite anodes to lithium to further lift energy density and reduce pack weight, though that adds its own challenges.

Solid-state batteries are expected to offer higher energy density, improved safety, faster charging and longer lifespan than current lithium-ion cells. Higher energy density can mean more range for the same pack size, or a lighter pack for the same range. Solid electrolytes can reduce leakage risk and improve heat tolerance. If the chemistry holds up, solid-state could also handle more rapid charging with less degradation, which matters for long-distance EV use.

Energy density is talked about because it affects everything from range to weight to cabin space. Add energy without increasing pack weight and size, and suddenly designers can squeeze more kilometres out of the same footprint. Or, they can maintain the range and drop pack size, which can help efficiency, braking and handling.

That said, the real-world win depends on the pack, not just the cell. Cooling systems, structure, and safety hardware all take space. If solid-state can simplify those supporting systems, the benefits compound.

Solid-state batteries are hard to commercialise because keeping the internal layers working smoothly is tricky. Lithium can still form dendrites that cause short circuits, and the solid electrolyte doesn’t “wet” the electrodes like a liquid does, creating resistance that slows performance. As the battery charges and discharges, parts can crack or separate, reducing life and power. Some materials also hate moisture, so manufacturing needs strict conditions. Making these cells reliably at automotive-scale volumes is still the main hurdle.

In most cases, yes. Most solid-state batteries still rely on lithium ions moving through the cell. The difference is the electrolyte, not the basic lithium chemistry. Many solid-state designs also aim to use a lithium-metal anode, rather than the graphite anode common in today’s EV batteries, because lithium can store more energy per gram. Some researchers are also exploring sodium-based solid-state batteries (sometimes referred to as salt batteries), but they’re much earlier in development and not the main focus for EVs right now.

Solid-state batteries are generally designed to be safer than conventional lithium-ion because they remove or reduce flammable liquid electrolytes, lowering leakage and fire risk. But they are not risk-free. Some chemistries can still suffer internal shorts or thermal runaway, especially if lithium dendrites penetrate the electrolyte. Safety still depends on cell chemistry, manufacturing quality, and pack design, rather than the “solid state” label alone.

Ultra-fast charging is where solid-state often gets pitched as the fix for EV sceptics. In theory, a stable electrolyte and lithium-metal anode could allow higher charge rates with less damage over time. In practice though, charging is where many solid-state problems show up first, because the interface is stressed hardest when ions are moving quickly.

It’s also why so many solid-state timelines talk about “pilot lines” and “validation” rather than ready-for-market promises. Running a handful of cells in a lab is one thing. Building thousands of defect-free cells that can survive years of fast charging is another.

They could be, but it’s not guaranteed. Solid-state batteries may reduce emissions per kilometre over a vehicle’s life if they deliver higher efficiency, longer lifespan, and fewer replacements. Higher energy density can also cut materials per kWh at pack level. On the other hand, some solid electrolytes require energy-intensive processing and strict dry-room manufacturing. Environmental performance will depend on the exact chemistry, factory energy source, and real-world cycle life.

As mentioned, there are a range of players in the solid state battery field, from carmakers to tech giants to startups. Honda, Nissan and Hyundai say they are developing their own production lines while other carmakers are generally doing so with tech partners. BYD straddles the gamut of carmaker and tech giant, as one of the largest battery makers in China with a 22 per cent market share.

Automakers investing heavily:

Tech giants and major cell makers:

Specialist solid-state developers:

The most realistic path is a slow rollout: limited production first, premium models next, then broader adoption only once cost and reliability line up with mainstream lithium-ion. Some makers are aiming for late-2020s production, with production pilots now planned.

Toyota says it has government approval for a pilot production line starting in 2026, which it will initially use in hybrids because smaller battery pack sizes would minimise investment costs. BMW has been testing solid-state batteries in a BMW i7 with battery specialist Solid Power and has now partnered with tech giant Samsung.

Meanwhile, China’s CATL is demonstrating "condensed matter" (semi‑solid) batteries (up to 500 Wh/kg) in aviation and high‑end EV applications, with mass production of semi‑solid cells also planned for later this year. BYD's SSB roadmap is targetting small-scale production in 2027, and 120,000 SSB vehicles by 2033. Lastly, Svolt is also planning a 2.3GWh semi-solid state battery production line in 2026 after completing trials and receiving orders from a major European customer.

However, history suggests solid-state deadlines are rarely on target. It seems the safest bet is to expect early solid-state EVs to appear in premium low-volume EVs to begin with by the end of the decade, before SSBs properly go mainstream.