Luke Sissons had no idea that a stroll down the Australian National University’s campus would spark a fascination that would eventually take him across the Outback behind the wheel of a solar car, competing in the world's premier solar powered car race, the Bridgestone World Solar Challenge.

During Orientation Week the aspiring physics student spotted the ANU Solar Racing Team’s 2023 vehicle 'Solar Spirit’ at one of the club tents – a first taste of the solar car race Australia is famous for – and after chatting to other team members, was hooked.

“It looked a bit like something sci-fi. I’ve always loved cars, watched Formula One, but more specifically aerodynamics. Thankfully, I got into the club and then … you kind of catch the bug for solar car racing.”

Now he is a Structures Team member and one of the drivers at ANU Solar Racing, and has just competed in the 2025 Bridgestone World Solar Challenge. The solar car race is as much an endurance test as a science project — long straights, brutal heat, and constant decision-making as the team balances speed, power use and weather.

Helping to design and build the chassis, Sissons says the experience has bridged the theory learnt in physics classes with solar vehicle development in the real world.

The ANU Solar Racing team is student run, with more than 40 undergraduates conceiving, designing and manufacturing their solar vehicles from scratch. Every two years they enter the BWSC: a 3,022-km endurance race from Darwin to Adelaide.

Monty, the team's most advanced solar car yet, features a multi-layered carbon fibre frame, a tailored solar array built in partnership with SunDrive Australia, and novel aerodynamics to tackle new race rules.

The NRMA’s sponsorship plays a vital role behind the scenes. This support helps relieve some of the financial costs that comes with building a solar car, while also giving the team visibility and media reach.

This year, Monty adopts an asymmetrical three-wheeled catamaran layout. “When the regulations came out, our interpretation led us believe that this was the best option. A massive part of that was the increase in the solar array surface area,” says Luke.

A surprising gain is Monty's ability to ‘sail’. “The major revelation we made with Monty was the sailing effect we could generate out of the aerodynamics. If you’re generating a thrust and getting up to speed in a more organic and natural way, it helps the efficiency of all the internal workings.”

Monty’s carbon fibre bodywork was manufactured in-house - a big step up for the team. “We worked alongside Composites, who are industry professionals, and they had a lot of insight into the smaller differences that make the biggest impact. One instance was the vacuum. Leakage in the vacuum bag makes a massive difference, so they showed us techniques to limit how much air was escaping.”

Luke admits there’s a special thrill in seeing a design materialise. “It was very rewarding seeing all these drawings and designs that were just on paper or on the computer finally being in front of you. It was very surreal.”

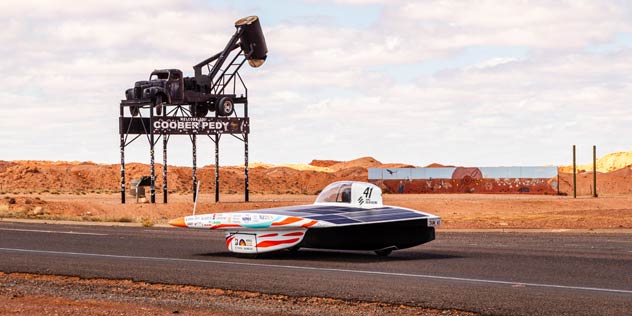

Testing in Coober Pedy exposed Monty to real-world environmental stresses. “Specifically it was definitely the gusts. That was a very big challenge, as well as how much dust there was. If dust starts mounting in the internals, it starts messing things up.”

With battery capacity limited under the new rules, energy management became a critical factor. “Battery management was a very big aspect of the race for us. I remember one control stop where it felt like army crawling to get over the line because the battery was depleting at a steady rate and we had to match the speed to make sure we weren’t using too much. We made that control stop with about a minute and a half left and everyone was very on edge.”

Communication also played a crucial role on race day. “During Coober Pedy we simulated our radio comms, getting those organised so drivers knew what they needed to do and people relaying information knew how best to say it. I was a driver myself, and personally I like a lot of information, no matter how big or small. That was the biggest application we carried into the race.”

“You’re dealing with a project of this scope with this kind of budget and the risk factors involved, so the importance of clear-cut communication and being able to work with others in an effective way has been massive,” Luke says. “ANU is predominantly a research school, so there aren’t a lot of practical scenarios. Being able to build something interesting and cool has been so rewarding.”

The project has also shifted his career thinking. “Part of my science degree is science communication … It informed me that I’m really passionate about the technical side of things, working through problems and understanding them, but also presenting that in a digestible and interesting way. That’s all been a result of being part of this project.”